This story was originally written in 1994 for a quarterly newsletter at Thurgood Marshall College, UCSD, called Diversity, Justice and Imagination. It was a remembrance of and tribute to my friend, John Hoagland, who had been a student there in the late '60s-early '70s, and was written in a voice addressing the current student body at TMC, who received the publication....

CAMERA WITH A CONSCIENCE

While accepting his Lifetime Achievement Award at the Thurgood Marshall College dedication ceremony on October 22, 1993, Carlos Blanco-Aguinaga unselfishly dedicated his award to students, "the ones who made the College." He talked about how hard they had worked and fought for their concepts of what this new school should become during the late '60s, sometimes at the expense of their own careers.

Carlos spoke the truth. I know because I was there. I'd like to tell you about one of those students. His name was John Hoagland.

John and I both came to UCSD from Helix High School in 1965, as part of the second undergraduate class admitted to Revelle College. It's difficult to describe what it was truly like on campus then, and probably nearly impossible to understand, even if you were there. The issues of social justice and inequality were so "in-your-face," fed by the civil rights movement and catalyzed by the war in Vietnam, that they were impossible to ignore. The political polarization of the community was nearly total. The rate of social change and the breakdown of authority seemed palpable and escalating daily.

San Diego was a new and very small campus, but was not without its share of activists asking, and eventually demanding, to know what the University was going to do to help in the struggle for freedom, justice and peace.

In 1967, Muir College had opened its doors. The planning for a third college campus was in full swing and the student body seized upon that as an issue. We demanded a voice in shaping what this third college would be and how it would be run. We had no idea how to build and run a college, but we had a burning desire to create an institution of higher learning that reflected our rising social consciousness, one that did not contribute to oppression and discrimination.

John had been involved in the student movement at UCSD, but only in a peripheral way until the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in 1968. This vicious act of murder galvanized him radically, changing his life forever. He joined the "Tuesday the Ninth Committee" on campus and helped organize a march into downtown La Jolla to protest the silencing of this great voice for equality. As a member of the Students for a Democratic Society, he fought along with the BSU and MEChA for the establishment of Lumumba/Zapata College. He stood guard duty at Dr. Herbert Marcuse's home after this learned and gentle professor of philosophy had received death threats from right-wing extremist groups in the community. He helped build the "People's Pot", a huge stainless steel urn in which communal stews and soups were cooked during the student strikes, to feed the hundreds of us who were literally living in Revelle Plaza. He generally dedicated himself to "the struggle" at the expense of his education and a comfortable future. But by a strange and simple twist of fate, he also found his destiny.

In 1970, John and a classmate appropriated a university vehicle and a bunch of video equipment under the guise of a project for their communications class and set out to document a peace march in East L.A. Rioting broke out and John ended up in the middle of a very heavy police action. He got some great footage but was separated from his friend, arrested and had the car confiscated by the police after the crowd was done abusing it.

Needless to say, there was some serious explaining to do, and his status as a student was put in jeopardy, but John didn't care. He wasn't really a very good student. His verbal skills were not all that strong and he actually hated math. But he had discovered the tools he needed to express himself, to capture images and convey to others the truth of his experience- his imagination and a camera!

He decided that he wanted to make photography his vocation. He thought of his camera in the same way that Woodie Guthrie thought of his guitar, as a "fascist-fighting machine." In 1977, he headed south to Central America as a photo journalist to try to help expose the suppression of the populist movements there.

He covered the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua and the conflict in El Salvador with a tenacity and courage which earned him respect and a reputation as a "combat" photographer. He would seek out and document the kind of action from which common sense tells most of us to flee.

He was careful not to propagandize with his photography. He just wanted people everywhere to witness through his work what was going on. His motto was: "Do something right and I'm going to take your picture. Do something wrong and I'm going to take your picture also."

John found himself too close to the action on several occasions. In 1980, the video cameraman with whom he was working was killed by a sniper. In 1981, he was riding in a car with several other journalists when they ran over a land mine set in the road. The explosion killed one of his colleagues and seriously injured another. John escaped with only minor injuries.

I saw him for the last time in 1982 when he returned to the States and stopped by my home in Del Mar. He wanted my advice in buying a new surfboard to take back down to El Salvador with him. He told me he was living in a little coastal town named La Libertad, and that there were some excellent, rocky, point breaks in the area that he wanted to surf when he had the time. He described his life there, which sounded to me like an insane combination of laid-back, tropical surf paradise shattered by occasional mind-bending moments of savage violence and the sheer horror of war.

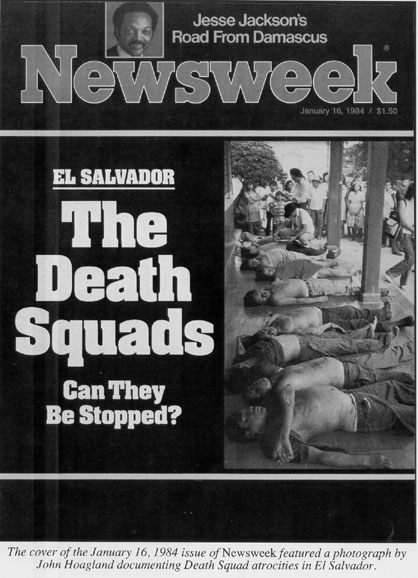

He headed back south, married a Salvadorean woman and eventually became the "dean" of foreign correspondents in El Salvador. He had been there longer than most and knew his way around well, often helping the "newbies" who would show up from other countries without a clue. His photos were published in the pages and on the covers of national and international magazines.

In 1983-84, he was sent on assignment to Beirut by Newsweek, which was a totally new and unfamiliar territory for him. Despite doubts about his ability to perform in a different arena, he pulled it off, getting cover shot credits again, then returned to his home in La Libertad.

On Mar. 16, 1984, he traveled with a CBS News crew towards a little town north of San Salvador named Suchitoto, running down a report of a firefight between the Army and guerilla forces. He was leading the approach to the action on foot when they were caught in a crossfire. A round from one of the Army's M-60 machine guns pierced his chest as he was taking pictures. The motor drive on his camera was still firing as he fell to the ground and died.

I saw the report on the evening news. I couldn't believe it, but at the same time I knew it was true. There was Dan Rather telling me my friend was dead.

So why am I telling you this story? I am trying to tell you something about ourselves, about the connections we have to other human beings and the obligation that brings to each of us. It was young people like John who cared enough, before most current Marshall students were born, to work and sacrifice to ensure that they would attend a different kind of college, one with a conscience.

I hope you will take advantage of the opportunities you have for public service and community involvement while you are here. By giving something of youself, you just may discover who you are.

Epilogue

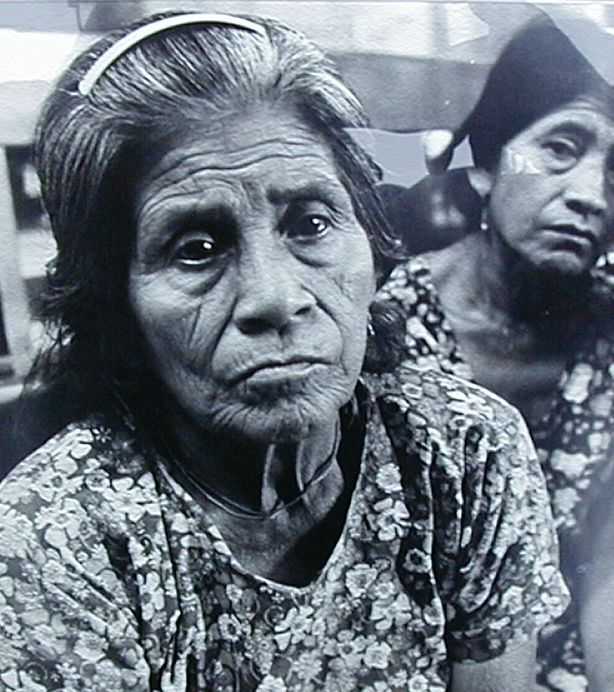

As I am creating this web page in Jan., 2004, one of John's photos hangs on the wall in my living room (sorry for the quality of the picture, as I did not want to take it out of the frame to scan it, this is a photo of it taken with my digital camera and cropped, thus the reflective artifacts in it):

In the mid-'80s, I was fortunate enough to see a documentary film of John's work in El Salvador called John Hoagland: Front Line Photographer, produced by David Helvarg and directed by Charles Landon. It was shown with a traveling exhibit of his photos called Two Faces of War at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as at the Grove Gallery at UCSD, while on loan from the Eye Gallery of San Francisco. I was able to meet his beautiful Salvadorean wife at this exhibition, after which I understand she returned to her native country, and see his parents again, who still live here in San Diego, as far as I know.

Sometime in the late '90s, I got a

call from his grown son Eros, whom he fathered with his first

wife while still a college student, and we met for an afternoon

of surf and conversation at La Jolla Shores. Eros was planning to

drive down to La Libertad himself, meet up with his stepmother,and

perhaps surf some of the cobblestone point breaks there which so

enthralled his father. Recently (2014), I visited with Eros again, and

found he was following in his father's footsteps, becoming an

accomplished "conflict photographer" himself. His website is http://www.eroshoagland.com/

Go to my HOME page